The condition tends to develop gradually, which means it can be mistaken for another, more common, condition at first.

The symptoms typically become more severe over several years, although the speed at which they worsen varies.

Some of the main symptoms of PSP are outlined below. Most people with the condition won't experience all of these.

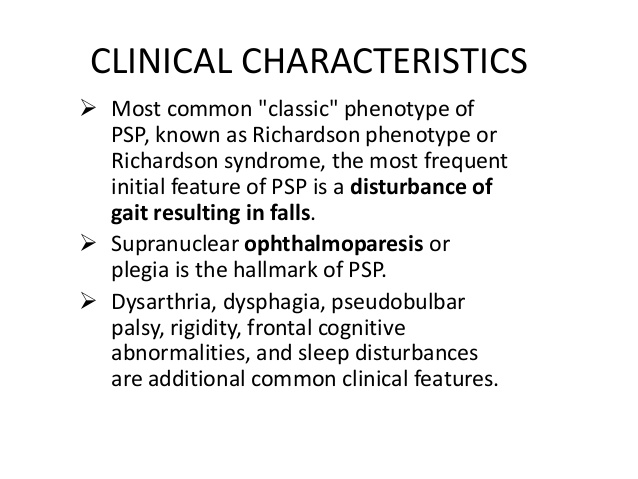

- The initial symptoms of PSP can include:

- sudden loss of balance when walking, that usually results in repeated falls, often backwards

- muscle stiffness, particularly in the neck

- extreme tiredness

- changes in personality, such as irritability, apathy (lack of interest) and mood swings

- changes in behaviour, such as recklessness and poor judgement

- a dislike of bright lights (photophobia)

- difficulty controlling the eye muscles, particularly problems with looking up and down

- blurred or double vision

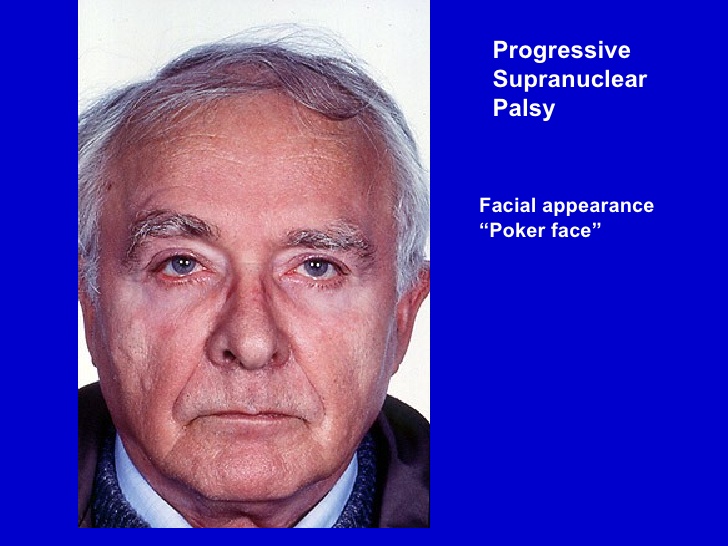

Some people have early symptoms that are very similar to those of Parkinson's disease, such as tremors (involuntary shaking of particular parts of the body) and slow movement.

Mid-stage symptoms

Over time, the initial symptoms of PSP will become more severe.

Worsening balance and mobility problems may mean that walking becomes impossible and a wheelchair is needed. Controlling the eye muscles will become more difficult, increasing the risk of falls and making everyday tasks, such as reading and eating, more problematic.

New symptoms can also develop at this stage, such as:

slow, quiet or slurred speech

problems swallowing (dysphagia)

reduced blinking reflex, which can cause the eyes to dry out and become irritated

involuntary closing of the eyes (blepharospasm), which can last from several seconds to hours

disturbed sleep

slowness of thought and some memory problems

neck or back pain, joint painand headaches

Advanced stages

As PSP progresses to an advanced stage, people with the condition normally begin to experience increasing difficulties controlling the muscles of their mouth, throat and tongue.

Speech may become increasingly slow and slurred, making it harder to understand. There may also be some problems with thinking, concentration and memory (dementia), although these are generally mild and the person will normally retain an awareness of themselves.

The loss of control of the throat muscles can lead to severe swallowing problems, which may mean a feeding tube is required at some point to prevent choking or chest infections caused by fluid or small food particles passing into the lungs.

Many people with PSP also develop problems with their bowels and bladder functions. Constipation and difficulty passing urine are common, as is the need to pass urine several times during the night. Some people may lose control over their bladder or bowel movements (incontinence).

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to diagnose progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), as there’s no single test for it, and the condition can have similar symptoms to a number of others.

There are also many possible symptoms of PSP and several different sub-types that vary slightly, making it hard to make a definitive diagnosis in the early stages of the condition.

A diagnosis of PSP will be based on the pattern of your symptoms and by ruling out conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as Parkinson's disease or a stroke.

Your doctor will need to carry out assessments of your symptoms, plus other tests and scans.

The diagnosis must be made or confirmed by a consultant with expertise in PSP. This will usually be a neurologist (specialist in conditions affecting the brain and nerves).

Brain scans

If you have symptoms of PSP that suggest there's something wrong with your brain, it's likely you'll be referred for a brain scan.

Types of scan that you may have include:

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan – where a strong magnetic field and radio waves are used to produce detailed images of the inside of the brain

positive emission tomography (PET) scan – a scan that detects the radiation given off by a substance injected beforehand

a DaTscan – where you're given an injection containing a small amount of a radioactive material and pictures of your brain are taken with a gamma camera

These scans can be useful in ruling out other possible conditions, such as brain tumours or strokes.

MRI scans can also detect abnormal changes to the brain that are consistent with a diagnosis of PSP, such as shrinkage of certain areas.

Scans that show the build-up of the tau protein in the brain that's associated with PSP are currently under development.

Ruling out Parkinson’s disease

You may be prescribed a short course of a medication called levodopa to determine whether your symptoms are caused by PSP or Parkinson's disease.

People with Parkinson's disease usually experience a significant improvement in their symptoms after taking levodopa, whereas the medication only has a limited beneficial effect for some people with PSP.

Neuropsychological testing

It's also likely you'll be referred to a neurologist and possibly also a psychologist for neuropsychological testing.

This involves having a series of tests that are designed to evaluate the full extent of your symptoms and their impact on your mental abilities.

The tests will look at abilities such as:

- memory

- concentration

- understanding language

- the processing of visual information, such as words and pictures

Most people with PSP have a distinct pattern in terms of their mental abilities, including poor concentration, a low attention span and problems with spoken language and processing visual information. Their memory of previously learned facts isn't usually significantly affected.

Coping with a diagnosis

Being told that you have PSP can be devastating and difficult to take in.

You may feel numb, overwhelmed, angry, distressed, scared or in denial. Some people are relieved that a cause for their symptoms has finally been found. There's no right or wrong way to feel – everybody is different and copes in their own way.

Support from your family and care team can help you come to terms with the diagnosis.