Most testicular cancer starts in the sperm-making cells of the testicles. Testicular cancer occurs most commonly in men aged 15 to 39 years.

Types of testicular cancer

The testicles are made up of many types of cells, each of which can develop into one or more types of cancer. It's important to know the type of cell the cancer started in and what kind of cancer it is because they differ in how they're treated and in their prognosis (outlook).

Doctors can tell what type of testicular cancer you have by looking at the cells under a microscope.

Germ cell tumors

More than 90% of cancers of the testicle start in cells known as germ cells. These are the cells that make sperm. The main types of germ cell tumors (GCTs) in the testicles are seminomas and non-seminomas.

These types occur about equally. Many testicular cancers contain both seminoma and non-seminoma cells. These mixed germ cell tumors are treated as non-seminomas because they grow and spread like non-seminomas.

Seminomas

Seminomas tend to grow and spread more slowly than non-seminomas. The 2 main sub-types of these tumors are classical (or typical) seminomas and spermatocytic seminomas.

- Classical seminoma: More than 95% of seminomas are classical. These usually occur in men between 25 and 45.

- Spermatocytic seminoma: This rare type of seminoma tends to occur in older men. (The average age is about 65.) Spermatocytic tumors tend to grow more slowly and are less likely to spread to other parts of the body than classical seminomas.

Some seminomas can increase blood levels of a protein called human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). HCG can be checked with a simple blood test and is considered a tumor marker for certain types of testicular cancer. It can be used for diagnosis and to check how the patient is responding to treatment.

Non-seminomas

These types of germ cell tumors usually occur in men between their late teens and early 30s. The 4 main types of non-seminoma tumors are embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and teratoma. Most tumors are a mix of different types (sometimes with seminoma cells too), but this doesn’t change the treatment of most non-seminoma cancers.

Embryonal carcinoma: These cells are found in about 40% of testicular tumors, but pure embryonal carcinomas occur only 3% to 4% of the time. When seen under a microscope, these tumors can look like tissues of very early embryos. This type of non-seminoma tends to grow rapidly and spread outside the testicle.

Embryonal carcinoma can increase blood levels of a tumor marker protein called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), as well as human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG).

Yolk sac carcinoma: These tumors are so named because their cells look like the yolk sac of an early human embryo. Other names for this cancer include yolk sac tumor, endodermal sinus tumor, infantile embryonal carcinoma, or orchidoblastoma.

This is the most common form of testicular cancer in children (especially in infants), but pure yolk sac carcinomas (tumors that do not have other types of non-seminoma cells in them) are rare in adults. When they occur in children, these tumors usually are treated successfully. But they're of more concern when they occur in adults, especially if they are pure. Yolk sac carcinomas respond very well to chemotherapy , even if they have spread.

This type of tumor almost always increases blood levels of AFP (alpha-fetoprotein).

Choriocarcinoma: This is a very rare and fast-growing type of testicular cancer in adults. Pure choriocarcinoma is likely to spread rapidly to other parts of the body, including the lungs, bones, and brain. More often, choriocarcinoma cells are seen with other types of non-seminoma cells in a mixed germ cell tumor. These mixed tumors tend to have a somewhat better outlook than pure choriocarcinomas, although the presence of choriocarcinoma is always a worrisome finding.

This type of tumor increases blood levels of HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin).

Teratoma: Teratomas are germ cell tumors with areas that, under a microscope, look like each of the 3 layers of a developing embryo: the endoderm (innermost layer), mesoderm (middle layer), and ectoderm (outer layer). Pure teratomas of the testicles are rare and do not increase AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) or HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) levels. Most often, teratomas are seen as parts of mixed germ cell tumors.

There are 3 main types of teratomas:

- Mature teratomas are tumors formed by cells a lot like the cells of adult tissues. They rarely spread. They can usually be cured with surgery, but some come back (recur) after treatment.

- Immature teratomas are less well-developed cancers with cells that look like those of an early embryo. This type is more likely than a mature teratoma to grow into (invade) nearby tissues, spread (metastasize) outside the testicle, and come back (recur) years after treatment.

- Teratomas with somatic type malignancy are very rare. These cancers have some areas that look like mature teratomas but have other areas where the cells have become a type of cancer that normally develops outside the testicle (such as a sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, or even leukemia).

Carcinoma in situ of the testicle

Testicular germ cell cancers can start as a non-invasive form of the disease called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or intratubular germ cell neoplasia. In testicular CIS, the cells look abnormal under the microscope, but they have not yet spread outside the walls of the seminiferous tubules (where sperm cells are formed). Carcinoma in situ doesn’t always progress to invasive cancer.

It's hard to find CIS before it becomes an invasive cancer because it generally doesn't cause symptoms or form a lump that you or the doctor can feel. The only way to diagnose testicular CIS is to have a biopsy . (This is a procedure to take out a tiny bit of tissue so it can be checked under a microscope.) Sometimes CIS is found incidentally (by accident) when a testicular biopsy is done for another reason, such as infertility.

Experts don’t agree about the best treatment for CIS. Since CIS doesn’t always become an invasive cancer, many doctors in the United States consider observation (watchful waiting) to be the best treatment option.

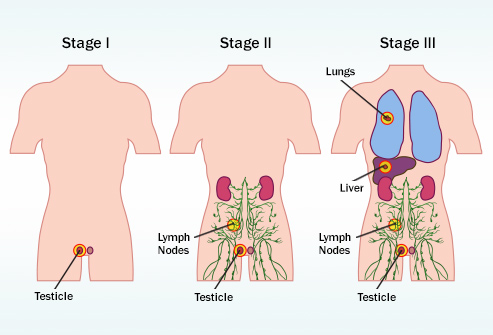

When CIS of the testicle becomes invasive, its cells are no longer just in the seminiferous tubules, they've grown into other structures of the testicle. These cancer cells can then spread either to the lymph nodes (small, bean-shaped collections of white blood cells) through lymphatic vessels (tiny fluid-filled tubes that connect the lymph nodes), or through the blood to other parts of the body.

Stromal tumors

Tumors can also start in the supportive and hormone-producing tissues, or stroma, of the testicles. These tumors are known as gonadal stromal tumors. They make up less than 5% of adult testicular tumors, but up to 20% of childhood testicular tumors. The main types are Leydig cell tumors and Sertoli cell tumors.

Leydig cell tumors

These tumors start in the Leydig cells in the testicle that normally make male sex hormones (androgens like testosterone). Leydig cell tumors can develop in both adults and children. These tumors often make androgens (male hormones), but sometimes they make estrogens (female sex hormones).

Most Leydig cell tumors are not cancer (benign). They seldom spread beyond the testicle and can often be cured with surgery. Still, a small number of Leydig cell tumors do spread to other parts of the body. These tend to have a poor outlook because they usually don't respond well to chemo or radiation therapy.

Sertoli cell tumors

These tumors start in normal Sertoli cells, which support and nourish the sperm-making germ cells. Like the Leydig cell tumors, these tumors are usually benign. But if they spread, they usually don’t respond well to chemo or radiation therapy.

Secondary testicular cancers

Cancers that start in another organ and then spread (metastasize) to the testicle are called secondary testicular cancers. These are not true testicular cancers – they don't start in the testicles. They're named and treated based on where they started.

Lymphoma is the most common secondary testicular cancer. Testicular lymphoma is more common in men older than 50 than primary testicular tumors. The outlook depends on the type and stage of lymphoma. The usual treatment is surgical removal, followed by radiation and/or chemotherapy.

In boys with acute leukemia, the leukemia cells can sometimes form a tumor in the testicle. Along with chemotherapy to treat the leukemia, this might require treatment with radiation or surgery to remove the testicle.

Cancers of the prostate, lung, skin (melanoma), kidney, and other organs also can spread to the testicles. The prognosis for these cancers tends to be poor because these cancers have usually spread widely to other organs as well. Treatment depends on the specific type of cancer.

What increases my risk for testicular cancer?

- One or both testicles did not descend (drop) into your scrotum

- A genetic disorder, such as Klinefelter syndrome

- A family history of testicular cancer

- Smoking cigarettes

What are the signs and symptoms of testicular cancer?

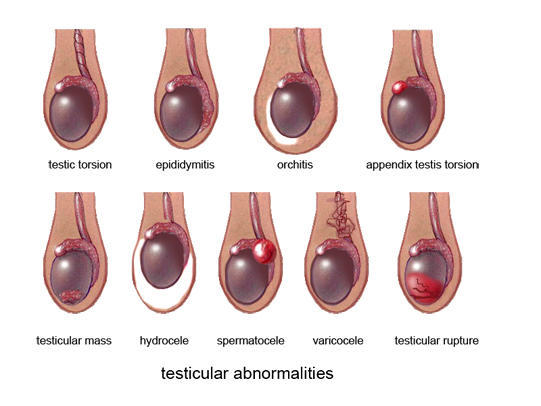

- A painless lump or change in how your testicle feels

- Your testicle becomes larger or smaller

- Swelling of your scrotum

- A feeling of heaviness in the scrotum

- A dull ache in the lower abdomen or in the groin

- Pain or discomfort in your testicle or scrotum

- Breast swelling or tenderness

How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider may shine a small flashlight on your scrotum. This may show a lump in or on your testicle. You may need one or more of the following tests:

- Blood tests may be used to check for cancer markers.

- An ultrasound or CT may show if the cancer has spread. You may be given contrast liquid to help the cancer show up better. Tell the healthcare provider if you have ever had an allergic reaction to contrast liquid.

- A biopsy may be used to take tissue from the testicle to be tested for the type of testicular cancer.

- Lymphangiography is a procedure that uses dye to see if the cancer has spread to your lymph nodes.

Will testicular cancer affect my ability to have sex?

A man with 1 normal healthy testicle can still have sex and make sperm. Before treatment, ask your healthcare provider how your ability to have sex may change. Treatment can affect these abilities. Some men have their sperm removed and frozen so that they can father a child at a later time.

How is testicular cancer treated?

- Surgery may be needed to remove your testicle. Lymph nodes that contain cancer may also be removed.

- Radiation therapy kills cancer cells and may stop the cancer from spreading with x-rays or gamma rays.

- Chemotherapy medicine is used to treat cancer by killing cancer cells. Chemotherapy may also be used to shrink lymph nodes that have cancer in them.

Treatment options

The following list of medications are in some way related to or used in the treatment of this condition.

- cisplatin

- Etopophos

- etoposide

- bleomycin

- Toposar

What can I do to manage my testicular cancer?

- Do not smoke. Nicotine can damage blood vessels and make it more difficult to manage your testicular cancer. Smoking also increases your risk for new or returning cancer and delays healing after treatment. Do not use e-cigarettes or smokeless tobacco in place of cigarettes or to help you quit. They still contain nicotine. Ask your healthcare provider for information if you currently smoke and need help quitting.

- Drink liquids as directed. Drink extra liquids to prevent dehydration. You will also need to replace fluid if you are vomiting or have diarrhea from cancer treatments. Ask your healthcare provider which liquids to drink and how much you need each day.

- Limit or do not drink alcohol as directed. Limit alcohol to 2 drinks per day. A drink of alcohol is 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1½ ounces of liquor.

- Eat healthy foods. Healthy foods include fruits, vegetables, whole-grain breads, low-fat dairy products, beans, lean meats, and fish. Ask if you need to be on a special diet.

- Exercise as directed. Exercise can help increase your energy level. Ask your healthcare provider about the best exercise plan for you.

How should I do a testicular self-exam?

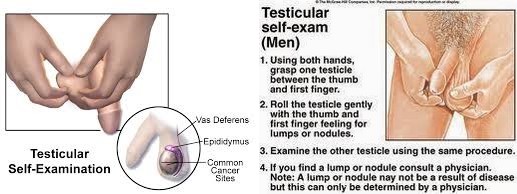

A testicular self-exam (TSE) can help you learn how your testicles normally look and feel. Ask your healthcare provider or oncologist for more information about a TSE and how often to do one.

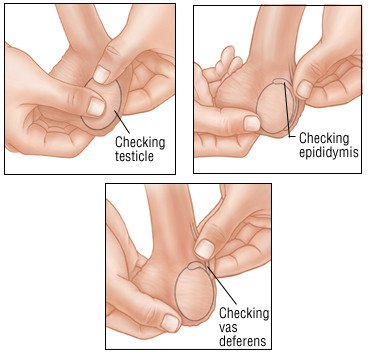

- Stand in front of a mirror and look at your scrotum. Look for changes in its shape, size, and color. It may be normal for one side of your scrotum to be larger or to hang lower than the other.

- Examine one testicle at a time. Put the thumbs of both hands in front of the testicle. Put the second (pointer) fingers behind the testicle. Gently roll each testicle between the thumbs and fingers of both hands. Feel for any lumps or changes in the testicle. It may be normal for one of your testicles to feel slightly larger than the other. Find a long, cord-like tube on top and in back of each testicle. This is the epididymis. Feel for any changes in the epididymis.

Call 911 for any of the following:

- Your leg feels warm, tender, and painful. It may look swollen and red.

- You suddenly feel lightheaded and short of breath.

- You have chest pain when you take a deep breath or cough.

- You cough up blood.

When should I contact my healthcare provider?

- You have a fever.

- You are confused or cannot think clearly.

- You are vomiting and cannot keep any food or liquids down.

- You feel lumps or other changes in your testicle.

- You are depressed and feel you cannot cope with your illness.

- You have pain that does not decrease or go away after you take your pain medicine.

- You have questions or concerns about your condition or care.